Andrew Safer has been practicing mindfulness meditation since he was 15 years old.

“I was living in Malibu, California, and my mother was always interested in different religions,” he says.

“She found a Zen monastery not far away and we went there for a weekend. We called it a family vacation. But I met the Zen master Suzuki Roshi there, and I started practising zazen meditation.”

He continued through university, where he met his teacher, a Tibetan Buddhist named Chogyam Trungpa. Safer practised with Trungpa for 14 years, until Trungpa’s death in 1987. He kept up with it, finding other teachers along the way. And now he’s a teacher himself.

A technical writer by trade, Safer leads a workshop series on mindfulness meditation at the Family Life Bureau, on Military Road. Since he began in 2010, he’s taught over 130 people.

“The mindfulness practice is rooted in the Buddhist tradition, when the Buddha sat down under a tree and stayed there until he understood,” he says.

“He evolved this way of working with his mind so that, when confronted with something that would normally freak us out, he was able to acknowledge them, deal with them and move on.”

But the mindfulness meditation that Safer teaches goes beyond Buddhism. His teachings are based on the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and founder of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care and Society.

“About 30 years ago, Kabat-Zinn was on a Buddhist meditation retreat,” says Safer.

“At the time, he was working in a hospital with people who suffered from a lot of chronic pain and stress, and he had this ‘A-ha!’ moment where he saw that meditation could be really beneficial for those people. So he figured out a way to introduce mindfulness in a secular context, without the trappings of any religion or culture.”

As it turns out, Kabat-Zinn was right, and there’s a growing body of work from neuroscientists to back him up.

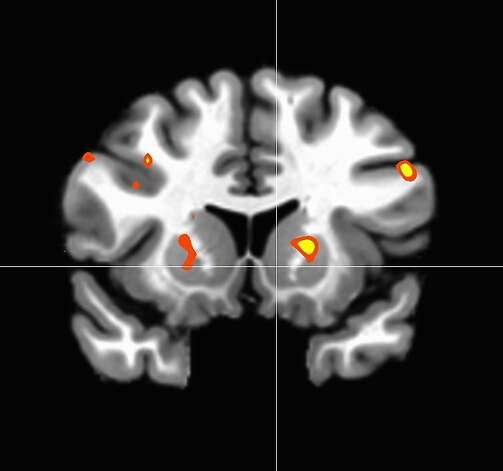

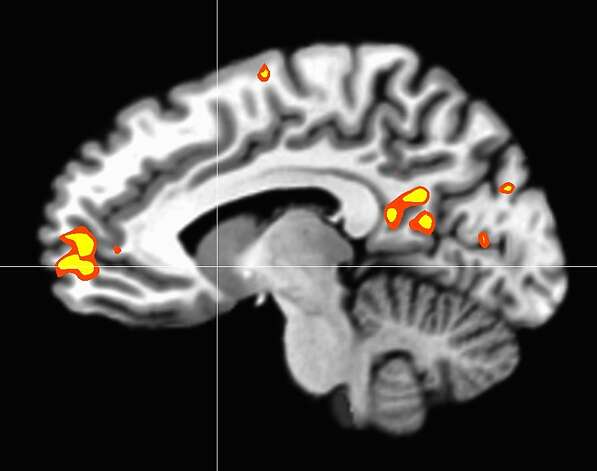

The prevailing theory to explain meditation’s role in pain and stress reduction centres on its interaction with the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.

The amygdala are two almond-shaped clusters of neurons located in the temporal lobes of the brain. They are associated with the processing of emotional reactions — the amygdala reacts quickly to stimulation, and it is the initiator of the “fight or flight” response.

Emotional signals are first received and processed by the amygdala, which then sends them to the prefrontal cortex at the front of the brain.

The prefrontal cortex is the brain’s voice of reason. It’s commonly associated with decision-making, differentiation between good and bad or right and wrong, and weighing consequences of actions and behaviours. Compared to the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex is slow and methodical.

“They say that as soon as that amygdala gets triggered, certain brain chemicals — adrenaline and cortisol, mostly — start surging through the body,” says Safer.

“That sends a message that we have to do something immediately, and we go into this reactive mode. Mindfulness meditation teaches us to give these thoughts and emotions some time and space. When we do that, we give our prefrontal cortex a chance to engage. Then, if we decide we’re going to do something about those thoughts or emotions, and we’re probably going to do something that’s far more reasoned,” he said.

Safer is particularly interested in how mindfulness meditation can help people suffering from mental illness, and he is in the process of developing an eight-week mindfulness meditation program that can be adapted for different conditions.

“There are lots of people who are suffering,” he says. “And not necessarily just those who have had a diagnosis, it could just be someone who is very anxious or is having trouble getting to sleep at night. A lot of it has to do with the past and the future: it could be something that you did and now you’re beating yourself up, or that you’re anticipating something in the future. The mindfulness practice trains us to actually be here, in the present.”

Ultimately, says Safer, mindfulness meditation teaches people to be better friends with their thoughts and with themselves.

“Nervousness, hesitation, self doubt — normally, when any of these feelings of discomfort come up, we try and avoid them,” he says. “But that approach doesn’t really work. This is more like acknowledging them and welcoming them. Treat these thoughts like guests, and welcome them into your house, but then welcome the next guest. We tend to get monopolized by our concerns or problems, and that’s like spending all your time on one guest.”

“Mindfulness meditation practice is about being non-judgemental in relation to everything that comes up in our mind,” he adds.

“It’s about not taking sides, and saying, ‘This is a good thought, this is a bad thought, this is what I should think.’ Treating our thoughts without judgement, treating them all the same, is an important form of loving kindness towards our ourselves.”

Interest in mindfulness is even spreading beyond medicine, he says, holding up a copy of a book called “A Mindful Nation: How a Simple Practice Can Help Us Reduce Stress, Improve Performance, and Recapture the American Spirit.”

“The author of this book is Tim Ryan, who is a United States congressman,” says Safer.

“He thinks, basically, that mindfulness can help rejuvenate America, and he talks about its possible applications in the health care system, in education and in the military. I haven’t seen anything about mindfulness on this scale before. So, I think it shows just how significant this practice can be.”

More information about mindfulness and Andrew Safer’s mindfulness meditation workshops can be found at

www.mindfulnesawareness.ca.

The website address is written incorrectly. It's there as: www.mindfulnesawareness.ca.

1) let go, nothing will go wrong, be free of your past, one thing at a time, throw your stick

2) learn what freedom is. be content where you are,"want to be there", enjoy the present

3) give and expecting nothing in return

4) have a teflon mind, collect no mementos, never allow knowledge to hide truth